In the 19th century, European powers divided Africa among themselves. Spain claimed the Western Sahara in 1884 and named it “the Spanish Sahara”.

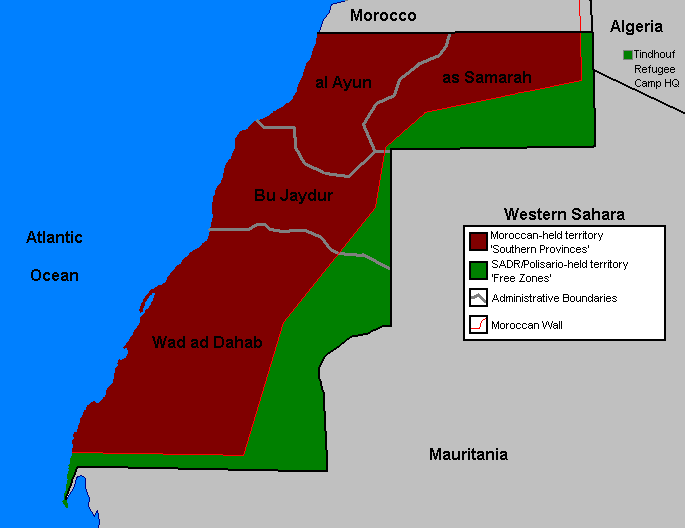

Located in the northwest of Africa, the territory is bordered by Morocco, Mauritania, and Algeria, and is home to the Sahrawi people.

Often referred to as Africa’s last colony, Western Sahara is rich in phosphate reserves, fisheries, and potential offshore oil, the very resources that made it attractive to Spain

Since Spain’s withdrawal in 1975, the region has been the centre of a territorial dispute. Morocco and Mauritania quickly moved in, claiming ownership. But the land was already inhabited, so how could they claim it?

Who rightfully owns Western Sahara? And why, after all these years, is the conflict still unresolved?

Pre-colonial Western Sahara and Its People

Before the arrival of the Spanish, Western Sahara was inhabited by Berber tribes. The area was historically populated by two major Berber tribes, namely, the Zenata and the Sanhaja. Sahwaris today are a mix of Berbers, Arabs, and Black African indigenes.

They were mostly nomadic, travelling across the desert with camels, herding livestock. For centuries, they were key players in trans-Saharan trade networks that connected West Africa with North Africa and beyond, exchanging goods like salt, gold, and textiles.

The Sahrawi spoke the Hassaniya dialect, a blend of Berber and Bedouin Arabic. Their society was shaped by tribal customs, Islamic teachings, and deep oral traditions passed through generations. Though the land was dry and unforgiving, it carried history, identity, and belonging.

They fiercely guarded their independence, resisting attempts at domination by external powers, including Moroccan sultans, as well as French and Spanish colonial interests.

The Rise of The Conflict

It’s 1975, and Spain finally pulls out of Western Sahara. Their withdrawal was fueled by many factors. The UN advisory opinion, along with pressure from Morocco and Mauritania. There was also notable resistance from the Polisario Front—a socialist Sahrawi group fighting for self-determination, along with international calls for decolonisation.

Earlier that year, Morocco and Mauritania took their claims to the International Court of Justice (ICJ). However, they were met with rejection.

The ICJ acknowledged that there were some historical ties (like religious allegiance or trade) between Sahrawis and both countries, but those ties did not amount to legal sovereignty. The two nations still proceeded to invade Western Sahara.

King Hassan II of Morocco organised the Green March in November 1975, sending over 350,000 Moroccan civilians into Western Sahara to stake a claim, completely ignoring the Sahrawi people’s aspirations for independence.

Shortly after the Green March, Spain signed the Madrid Accords, a shady deal that handed administrative control of the region over to Morocco and Mauritania without consulting the Sahrawi people.

In 1976, the Polisario Front declared the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) an independent state. Although the UN does not recognise the SADR, it has received partial international recognition; 46 UN member states have recognised it, and it is a full member of the African Union.

The Polisario Front launched an armed insurgency, targeting Moroccan and Mauritanian troops in a bold fight for Sahrawi independence. What started as scattered attacks quickly escalated into a full-blown 16-year war across the desert.

Mauritania initially claimed the southern portion of Western Sahara, citing ethnic and historical ties to the region known as Bilad Chinguetti. However, after facing heavy military pressure from the Polisario Front, Mauritania signed a peace agreement with them in 1979 and officially renounced all territorial claims.

After Mauritania’s withdrawal, Morocco swiftly moved in and annexed the area, claiming sovereignty over the entire territory of Western Sahara. This move remains unrecognized by the United Nations and is considered a violation of international law.

The War (1975–1991)

The years that followed were marked by a long guerrilla war, fought from the sand and shadows behind enemy lines.

The Polisario, backed by Algeria and Libya, struck Moroccan military targets and supply lines. Morocco, better armed, responded with airstrikes, napalm, and phosphorus bombs.

About 14,000 people lost their lives during the war, including around 5,000 Moroccan soldiers, 2,000 from Mauritania, 4,000 Polisario fighters, and roughly 3,000 civilians.

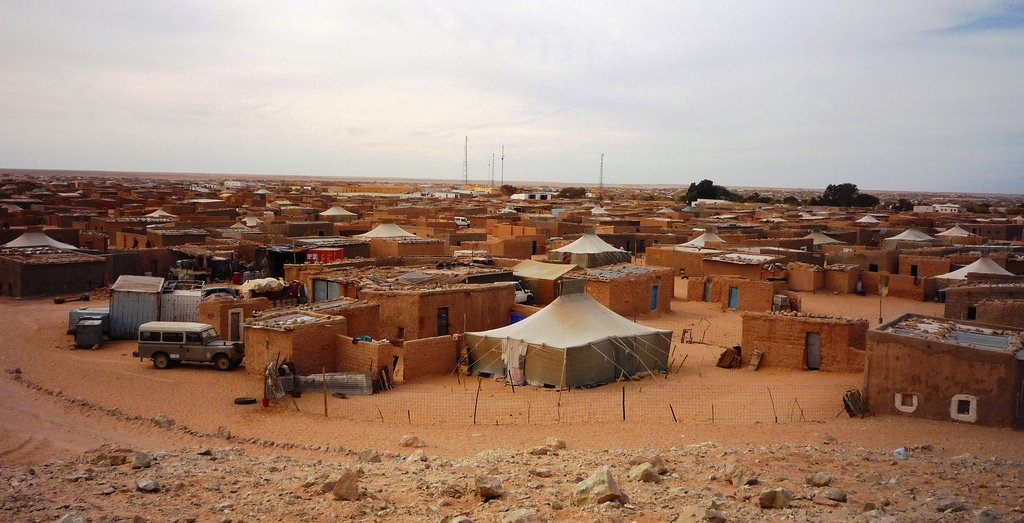

The war displaced tens of thousands of Sahrawis. Refugee camps were set up in Tindouf, Algeria—meant to be temporary shelters, but still stand to this day.

In response to the growing insurgency, Morocco began building a sand wall, “the Berm”, stretching over 2,700 km across the desert.

Lined with landmines, the wall divided the territory and entrenched the occupation. According to the United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS), Western Sahara is among the most heavily mined regions globally, with more than 2,500 people killed or injured since 1975.

A UN-brokered ceasefire came in 1991. They established MINURSO (United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara), which would allow the Sahrawis to finally vote on their future. However, the referendum never took place, primarily due to disputes over voter eligibility, which resulted from the Green March’s introduction of Moroccan settlers into Western Saharan territory.

Morocco and the Polisario Front have long disagreed on who should be allowed to vote. Morocco wants settlers included, while the Polisario insists on limiting it to the original Sahrawi population.

Where Things Stand Today

In 2020, Polisario declared the 1991 ceasefire void after Moroccan forces breached a buffer zone. Armed clashes have since resumed.

Morocco controls over 80% of Western Sahara and treats it as its “Southern Provinces”. It has built infrastructure, offered citizenship, and encouraged settlement to solidify claims.

The United States of America, under the Trump administration in December 2020, formally recognised Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara. This controversial move was part of a broader deal in which Morocco agreed to normalise relations with Israel.

The UN still considers Western Sahara a “non-self-governing territory”. The long-promised referendum? Still postponed, entangled in disputes over who counts as a legitimate voter.

In the meantime, the wall, “the Berm”, still splits the land. Landmines litter the desert. And Sahrawis remain scattered, some under occupation, others in exile.

Humanitarian Impact

After 50 years, many Sahrawi families remain in exile. Over 170,000 people live in refugee camps near Tindouf, a remote region in the harsh Algerian desert where temperatures soar above 50°C and water is scarce.

Morocco has disputed these figures, arguing that they may be inflated to increase aid and political leverage.

These camps, managed by the Polisario Front, the Sahrawi independence movement, and the government in exile, have developed into semi-permanent towns.

There are five refugee camps in total: Layoune, Aousserd, Boujdour, Smara, and Dakhla. The Sahrawi population in these areas relies almost entirely on humanitarian aid.

Youth born after the ceasefire have never seen their homeland. With few opportunities, education and resilience have become both tools of survival and subtle resistance.

Malnutrition, limited healthcare, and droughts worsen an already fragile existence.

Meanwhile, within Moroccan-occupied Western Sahara, a difference in opinion is met with surveillance, arrests, and torture. Sahrawis who protest the occupation risk imprisonment or worse.

A Land in Waiting

Spain’s withdrawal left a political vacuum, and instead of independence, the Sahrawis got new occupiers. The UN promised a referendum, which is yet to happen, and the rest of the world looked away.

The story is layered with betrayal, resilience, and geopolitical silence. To be Sahrawi today is to live in between. You’re not Moroccan, nor are you fully free. Entire generations have grown up in camps, caught between peace and frustration. Some cling to hope. Others see armed struggle as the only way forward.

So, when does this conflict end? And when do the Sahrawis finally get the chance to reclaim their land?

About The Atlas

The Atlas is a blog by Kharita, dedicated to exploring topics in geography, history, and geopolitics, without the typical Western spin. We aim to offer fresh, grounded perspectives and welcome contributions from writers around the world, representing a diverse range of experiences and backgrounds.

عن الأطلس

الأطلس هو مدونة تابعة لـ خريطة، مخصصة لطرح مواضيع في الجغرافيا، والتاريخ، والجغرافيا السياسية، من غير الفلترة أو التحيز الغربي المعتاد. هدفنا هو تقديم رؤى جديدة وواقعية، وبنرحب بمقالات من كُتّاب من مختلف أنحاء العالم، بخلفيات وتجارب متنوعة.