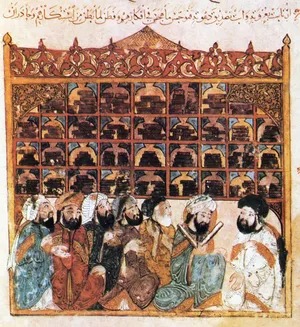

“Bayt al-Hikmah”, “House of Wisdom”, is a central institution in Islamic intellectual history. Some think that it represents the mental transformation that took place in the Islamic world. Bayt al-Hikmah flourished within the Abbasid caliphate between the 8th and 10th centuries. This center played an important role in the intellectual development of a time often considered as “the Golden Age of Islam”. This prosperity was a deliberate, state-sponsored initiative. This reflects the strategic investment in knowledge by Abbasid leaders.

Baghdad, the Abbasid capital, has become a dynamic cultural and scientific center. The cosmopolitan city has hosted researchers and scientists from several religions and ethnicities. This was crucial for the influx of foreign cultural and intellectual elements into the Arabic language. Bayt al-Hikmah was developed by several successive Abbasid caliphs. Al-Mansur (r.754-775) initiated the movement by founding new institutes in Baghdad and acquiring many books. Harun al-Rashid (r. 786-809 CE) continued in this direction. He acquired foreign books and encouraged scientific exchanges.

Lost In Translation

Al-Mansur adopted several aspects of the Sassanid imperial ideology. Among these is a well-designed administration. He thus bet that the Persians, imbued with Sassanid culture, would be faithful to the Abbasids. Under Al-Mansur, then Al-Mahdi, Persian families were active in the high ranks of the Abbasid administration. Among these families, the Barmakids and the Nawbaht are perhaps the most well-known.

Another aspect of the Sassanid ideology adopted by al-Mansur is based on the concept of «recovery». The Sassanid dynasty had already translated ancient works into Pahlavi. This activity was therefore continued by al-Mansur from the Pahlavi in Arabic. The bearers of this translation culture, therefore, held high positions in the administration.

The institution reached its peak under the reign of al-Ma’mun (813-833). The latter has officially made the House of Wisdom a translation office. Al-Ma’mun also institutionalized it by giving regular salaries and opening it to the public. The caliph has significantly strengthened his scientific activities. For example, he sent delegations to the Byzantine libraries to get manuscripts. Not merely intellectual, the translation activities responded to broader political and religious objectives.

From Translation to Innovation

Bayt al-Hikmah set its legacy with the translation movement, but the works of the scholars did not end there. As more texts were translated into Arabic, the house soon came to include additional research in areas of science, math, and astronomy. They used the newly translated texts to push forward with these innovations. Baghdad became a vibrant city, which helped it attract scholars from all over to contribute to this new age. These translators and scholars were encouraged to continue these works in Arabic. Their payments were the equivalent weight of the books in gold.

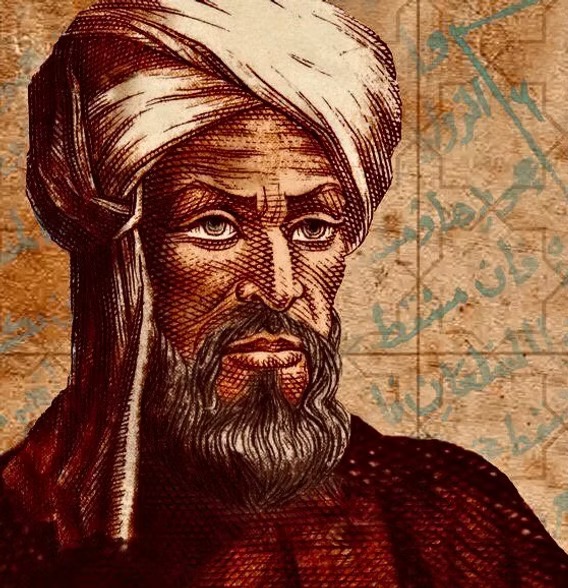

One of the most notable figures from this era was Al-Khwarizmi. Al-Khwarizmi drew inspiration from Greek geometry and Indian numerals. He wrote Al-Kitab al-mukhtasar fī hisab al-jabr wal-muqabala, which laid the foundation for algebra. The word, algorithm, comes from the latin version of his name. Many notable scholars from this age, like Al-Khwarizmi, who were able to take these newly translated texts and use them to develop new research. Original research and innovation was encouraged as the house expanded beyond simply being a library.

Beyond the Myth

The idea that prevails when talking about the Bayt al-Hikmah is that it was a great center for Greek-Arabic translation, an efficient academy, or a conference center. Dimitri Gutas, in Greek culture, Arabic thought, proposes a re-reading of this idea. He suggests reducing the role of Bayt al-Hikmah. This proposition is based on the available historical evidence.

Firstly, the term «Bayt al-Hikmah» itself is the translation of a Sassanid term. The meaning designates a library designed to bring together historical and poetic books of royalty. This was done regularly in the Sassanid ideology, which the caliph al-Mansur decided to adopt. Secondly, it follows that the initial function of Bayt al-Hikmah was to gather and ease the translation of Persian books into Arabic. The reports describing translation activities in the Bayt al-Hikmah mention translations from Persian, not Greek. Thirdly, we have information that describes the Bayt al-Hikmah developing additional activities. For example, as we have seen, there is talk of research in astronomy and mathematics, with al-Khwarizmi or Yahya ibn-Abi-Mansur. However, there is no detailed information on the exact nature of these activities, except for research and study.

Finally, we kept many reports that detail the Greek-Arabic translations, but none mention the Bayt al-Hikmah. One can thus believe that his contribution to the Greco-Arabic translation movement was indirect. Maybe by creating an environment where these translations were tolerated. The research concerning Bayt al-Hikmah is, therefore, plagued by a constant lack of evidence. That is why Gutas writes (p. 59) :

“ It was certainly not a center for the translation of Greek works into Arabic; (…) and certainly also not an “academy” for teaching the “ancient” sciences as they were being translated.”

The End Of Bayt al-Hikmah

The House of Wisdom was unfortunately destroyed around 1258 CE by the Mongols. While the Mongols slaughtered the scholars, they spared the Caliph as they wanted him to witness the destruction. They forced him to watch as they threw the texts and books into the Tigris. Some say that the river turned red and black from the blood and the ink.

The destruction of Bayt al-Hikmah is often comparable to the burning of the Library of Alexandria back in 48 BCE. Although many claim that the burning of the library was not intentional, the results remain the same. Centuries of accumulated knowledge, innovation, and culture are lost forever. Alexandria’s decline was gradual, while the House of Wisdom was destroyed quickly by the Mongols. They didn’t just destroy the books; they slaughtered the scholars and poets, bringing down the entire intellectual system.

For Baghdad, this attack marked the end of the Islamic Golden Age, an era that spanned from around the 8th to the 13th century. During this era, Baghdad had become a vibrant city, bringing together scholars and poets from all over the world. The destruction was devastating, not just for the city but for the academic world. The preservation of knowledge is not just an academic concern. Bayt al-Hikmah showed us how quickly centuries of knowledge can be destroyed.

Bibliography

Gutas, D. (1998). Greek thought, Arabic culture: The Graeco-Arabic translation movement in Baghdad and early ʻAbbasid society (2nd-4th/8th-10th centuries). Routledge.

Hannawi, A. A. (2012). The role of the Arabs in the introduction of paper into Europe. MELA Notes, (85), 14–29. [suspicious link removed]

Kamaly, H. (1999). [Review of Greek Thought, Arabic Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early ’abbasid Society (2nd-4th/8th-10th Centuries), by D. Gutas]. Iranian Studies, 32(4), 575–578. [suspicious link removed]

Nor, M. R. M. (2012). The significance of the Bayt Al-Hikma (House of Wisdom) in early Abbasid Caliphate (132 A.H-218 A.H). Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research, 11(9), 1239-1246. https://doi.org/10.5829/IDOSI.MEJSR.2012.11.09.22709

Taş, İ. (2011). A transformation in Islamic thought: The House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Hikmah) in the context of Occidentalism versus Orientalism. IDEA – Studia nad struktura i rozwojem pojec filozoficznych, XXIII, 245–270.

Zou’bi, M. R. (2017). Science institutionalization in early Islam: “Bayt al-Hikma of Baghdad as a model of an academy of sciences”. Dirasat, 44 (3).

About The Atlas

The Atlas is a blog by Kharita, dedicated to exploring topics in geography, history, and geopolitics, without the typical Western spin. We aim to offer fresh, grounded perspectives and welcome contributions from writers around the world, representing a diverse range of experiences and backgrounds.

عن الأطلس

الأطلس هو مدونة تابعة لـ خريطة، مخصصة لطرح مواضيع في الجغرافيا، والتاريخ، والجغرافيا السياسية، من غير الفلترة أو التحيز الغربي المعتاد. هدفنا هو تقديم رؤى جديدة وواقعية، وبنرحب بمقالات من كُتّاب من مختلف أنحاء العالم، بخلفيات وتجارب متنوعة.