How Colonialism Changed Our Borders Forever

Arya Srivastava

“No one can be a true nationalist who is incapable of feeling ashamed if his or her state or government commits crimes including those against their fellow citizens.”

- Benedict Anderson

Modern nation-states are often thought of in terms of what one might call the “Sleeping Beauty metaphor”, the belief that the nation had always existed, simply awaiting its historical awakening. This metaphor, which gained popularity following the events of the Glorious and French Revolutions, was projected onto colonized states, where such thoughts had never existed. In these places, nationalism wasn’t a natural sentiment that people had. It was built. It took ideas from Europe and mixed them with local resistance against the empire. This kind of postcolonial nationalism didn’t come from a shared history. It stemmed from the decision of what to remember and what to forget. Colonial powers helped shape this by drawing new borders, breaking up old communities, and changing how people thought about the past.

Benedict Anderson’s idea that nations are “imagined communities” becomes important when one talks about the colonial world, where the imagination itself was controlled. This article explores how geographical location and political power enabled this violent imagining. Focusing on India, China, and the Middle East, it asks: What parts of history had to be erased to build new nation-states? How did borders change our history?

How Colonial Maps Created Modern Nations

Borders were not merely physical boundaries drawn for the convenience of colonial powers, but tools of imperial control and identity-making. Colonial mapping practices sought to construct nations by dividing and erasing. Arjun Appadurai, in his remarkable essay, The Production of Locality, argues that colonialism changed how people saw themselves as well as different communities. It created new ways for people to belong, but only under the control of the empire. The colonial government used tools like surveys and censuses to sort people into fixed groups. These groups were not based on real life, but on labels like religion, caste, and ethnicity. This helped the state control people by putting them into clear boxes.

In the Middle East, the colonial authority used borders to control people without thinking about the various cultures, religions, and tribes. The 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement is one example. It drew boundaries across the region, creating countries like Iraq by forcing different groups together. These borders caused long-lasting tensions and made it harder for people to live peacefully. In India, British rule made old conflicts worse and also created new ones. They drew maps based on religion, which pushed Hindus and Muslims further apart.

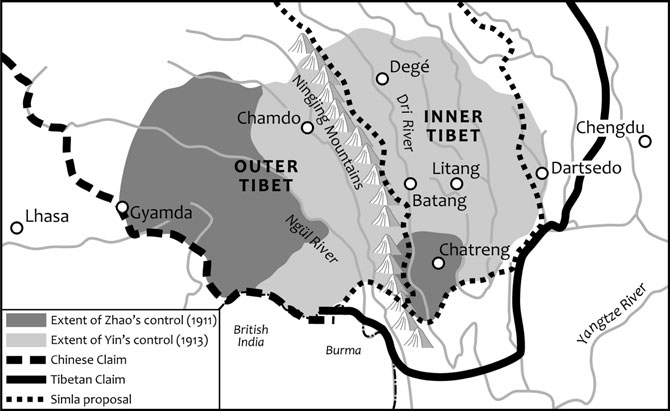

These groups were treated like they had always been separate, but that idea was made up during colonial rule and enforced by communal politics. It was used to break up a pluralistic society by focusing on differences instead of connections. Scholar Mahmood Mamdani explains that colonial rulers turned flexible identities into strict categories. Through indirect rule, they made culture part of law and government, deciding who got rights and who didn’t based on things like religion or ethnicity. This wasn’t simply paperwork, it was a way to control power and movement. Even when colonial powers didn’t draw the borders themselves, they still had a big impact. In China, for example, British policies shaped the border with Tibet. The 1914 Simla Conference treated Tibet as autonomous but didn’t call it fully independent. This created confusion and made Tibet a buffer between British India and China, setting up problems that would last for years.

Once borders are understood not as neutral territorial divisions but as tools of imperial governance, it becomes essential to recover the variety of histories that were erased in the process; histories suppressed to legitimize the formation of new nation-states.

Chinese and Tibetan territorial claims at the Simla Conference (1914)

Erasure as Foundation

Ernest Gellner, in his theory of nationalism, said that modern societies often force one main culture onto everyone. This “high culture” pushes out local stories, languages and traditions, which he called “low culture.” After colonial rule ended, many new countries kept using the same idea. They built national identities based on one ideal type of citizen, often copying the same powers they had fought against. In the Middle East, this can be seen clearly. Arab governments in places like Iraq and Syria often ignored or denied Kurdish identity. In Israel, the government used maps, schools and laws to remove signs of Palestinian life and history. Writer Nur Masalha, in The Politics of Denial, explains how this was done to support a new national story and erase the old one.

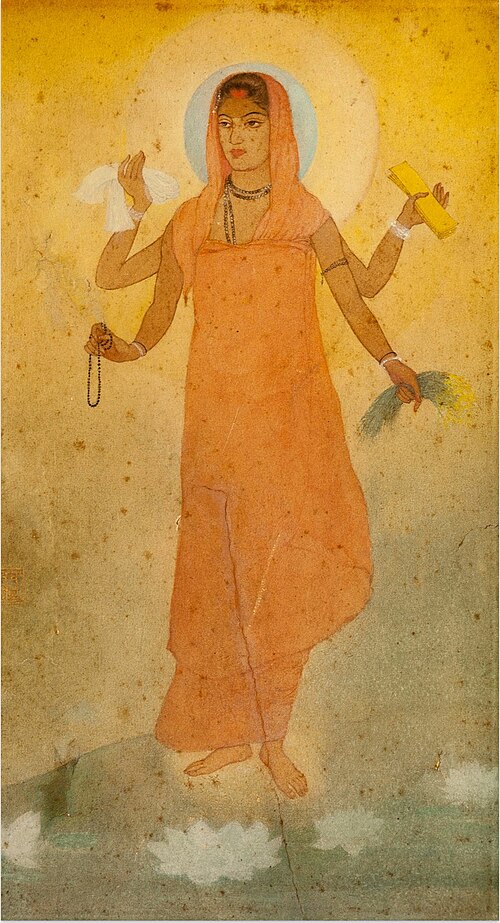

In China, school textbooks have been changed to remove Tibet’s separate culture, language, and religion. Instead, Tibet is shown as always being a part of China’s main Han identity. In India, the nation’s story was also shaped in a narrow way. Nationalist history often focused on Sanskrit and upper-caste Hindu traditions. Historians like Gyanendra Pandey and Shahid Amin show how cities like Lucknow and Delhi, cultural centres of Indo-Islamic traditions, were made to seem weak or backward. This idea was supported by images like Bharat Mata or Mother India – a Hindu goddess shown as calm, pure and ascetic. While this image was used to unite people, it also left out other religions and stories of the nation.

Bharat Mata (Mother India) by Abanindranath Tagore (1871-1951)

Memory and Resistance

Governments often tell stories about the past that seem simple and complete. These official histories leave out details, ignore suffering, and try to hide conflict. But memory doesn’t always follow the state’s version. In many places after colonial rule, people remember in ways that go against what they are told. Edward Said, in Culture and Imperialism, said that remembering is a way to resist. Memory can break the image of a perfect nation and bring back voices that were pushed aside. In the Middle East, Palestinian communities use memory to fight back. Oral stories, Nakba events and family histories remind people of the homes and livelihoods they lost. Kurdish music and writing do the same, keeping culture alive even when governments try to silence it. These are ways of standing up to erasure.

In India, Dalit oral stories have worked like a second archive. They speak of caste violence and survival. Thinkers like Kancha Ilaiah have shown how upper-caste stories often erase these truths. Filmmaker Pa Ranjith brings Dalit history into public view, reclaiming space through film. Partition memories also break the idea that the nation was born swiftly. Manto’s short stories such as Toba Tek Singh show how borders made no sense to the people living through them. Khol Do tells the story of gendered violence that states refused to name. Urvashi Butalia’s The Other Side of Silence shows how Partition is remembered in whispers, often by women, often outside official records. In China, exiled Tibetan communities have used poems and art to hold on to identity. Poet Tsering Woeser writes about the loss of Tibetan culture, language, and religion. Her memory is personal as well as a protest. All these stories remind us that history is not neutral. What gets remembered, and what is erased, is always about power.

Band playing at the Turkish barracks near the Jaffa Gate in Jerusalem, 1903

Our History, Their History, Whose History?

Colonial maps were never just about drawing boundaries and marking territories. They were used to create differences and control space. By changing borders, renaming places, and putting people into fixed groups, the empire disrupted older ways of habitation and forced new divisions between communities and their histories. These changes made it seem like people were always separate, even when they weren’t. As Homi Bhabha said, colonial rule shaped how populations saw themselves. The map thus became more than a picture of land. It told people who they were and where they belonged. After independence, many new countries kept these divisions in the name of unity. But memory doesn’t follow straight lines. Stories, art, and protest show that real lives don’t fit into the map’s clean boxes. Colonial borders still shape how we remember, but they can’t fully control how we take our past back.

About The Atlas

The Atlas is a blog by Kharita, dedicated to exploring topics in geography, history, and geopolitics, without the typical Western spin. We aim to offer fresh, grounded perspectives and welcome contributions from writers around the world, representing a diverse range of experiences and backgrounds.

عن الأطلس

الأطلس هو مدونة تابعة لـ خريطة، مخصصة لطرح مواضيع في الجغرافيا، والتاريخ، والجغرافيا السياسية، من غير الفلترة أو التحيز الغربي المعتاد. هدفنا هو تقديم رؤى جديدة وواقعية، وبنرحب بمقالات من كُتّاب من مختلف أنحاء العالم، بخلفيات وتجارب متنوعة.

4 thoughts on “How Colonialism Changed Our Borders Forever”

Very well articulated- loved it

Incredibly informative and well written

Absolutely loved reading it. Thought provoking and comes out as very well researched article.

Thought provoking and very well articulated