If you went to school in Egypt, you probably know the name Denshawai. It might bring back memories of a history lesson. You may recall bullet points from a revision booklet or a multiple-choice question on the subject. The narrative presented was so clear that it might surprise you to hear that it wasn’t the only one in existence at the time of the infamous incident. British stories about Fellaheen, or Egyptian country farmers, helped make the events possible. It might also surprise you to hear that Denshawai fanned the flame of Egyptian nationalism for decades to follow. If none of these events ring a bell, allow us to walk you through the events of the 13th of June, 1906.

What Happened in Denshawai?

The incident took place in a village in the Menoufia governorate in Egypt called Denshawai. British soldiers from the 6th Dragoons marched through the village. They began hunting pigeons for sport. A scuffle broke out, and an officer’s gun was fired. Four villagers were injured, including one woman. One officer escaped the struggle and made his way back to the British camp on foot under the noontime summer sun. He collapsed and died, likely due to heatstroke. A villager came to his assistance but was seen by other soldiers and believed to have killed him; in turn, the villager was killed.

The Trial

On June 24, just 11 days after the incident, authorities arrested 50 villagers. They were tried for murder. Twenty-one were found guilty. Four were hanged publicly, seven were flogged, and the rest received different prison sentences. These sentences were reached under a tribunal that was not bound by the constraints of the reformed penal code that the English had created. The reformed penal code phased out flogging and the death penalty as sentences. British officials, particularly Lord Cromer, defended the strict trial rulings. They believed that Egyptians would ignore a tribunal that abandoned these practices. Lord Cromer later resigned as consul-general after facing backlash for its severity.

How Could This Happen?

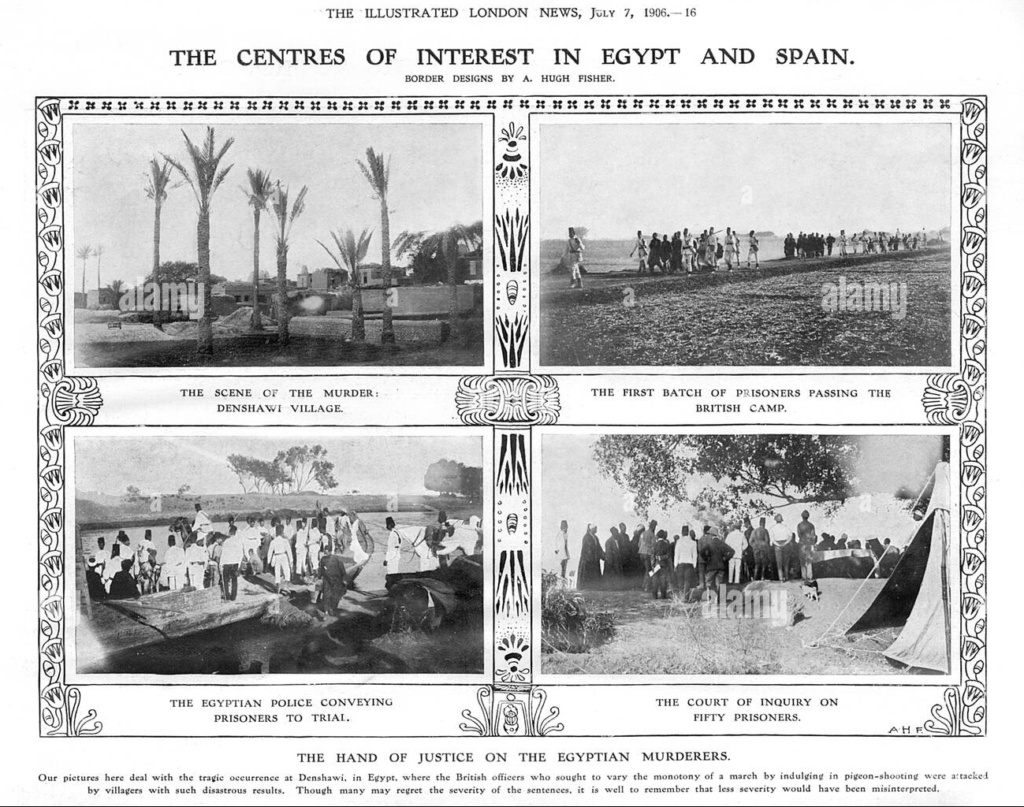

This justification is built on the same assumptions common to colonial narratives of any native population. In this case, British narratives and stereotypes of Fellaheen. These assumptions are evident in British coverage of the incident. An excerpt from The Illustrated London News, displayed below, overflows with these biases. The 4 villagers sentenced to death are described as ‘the ringleaders”, the rest as “murderers”. This language carries connotations of innate evil and savagery.

Most sinister of all is the smallest piece of text at the bottom of the image, providing the same justification discussed earlier. “It is well to remember that less severity would have been misinterpreted”, as though the “hand of justice” of British colonialism is needed by the people of Denshawai, that without it, they would lack a sense of morality and justice.

The Egyptian Gazette, Egypt’s only English paper at the time, wrongly framed the officers’ actions. They described it as “varying the monotony of a march by indulging in pigeon shooting.” This portrayal, plus the labeling of the villagers’ reaction as “unprovoked,” is inaccurate and unfair. Irish playwright and activist Bernard Shaw noted that the livelihood of the villagers relied on the pigeons. He compared their importance to that of poultry for an English farmer. He asks the reader to imagine “the feelings of an English village ” if their ducks, geese, hens, and turkeys were shot at.

What Was Denshawai To Egyptian Nationalists?

On the Egyptian side, previously struggling anti-colonial and nationalist movements were set ablaze. From this view, the villagers were not seen as uncivilized murderers. In fact, they were not even thought to have killed the soldier. They were viewed as villagers whose response was fair and justified. Their livelihoods were under threat. The trial was seen as unjust and became a notorious example of the cruelty of colonial rule.

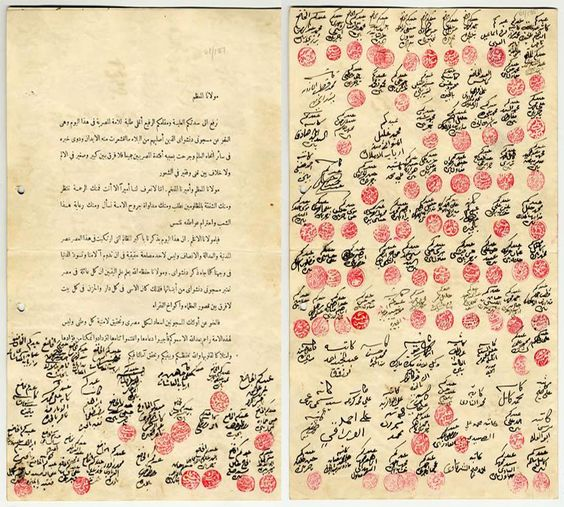

Nationwide outrage is captured in countless pieces of poetry and news articles written in the aftermath of the incident. Notable examples include the poetry of Ahmed Shawky and Hafez Ibrahim. Also, reports from the infamous Al Liwa newspaper, founded by journalist and nationalist activist Mustafa Kamel, stand out. Pleas were made in poetry expressing the people’s desire for the release of the prisoners. Formal appeals were made. Botros Ghali, Egypt’s justice minister then, was one of the five judges on the case. He was assassinated. His assassin favored the British during the trial as one of his motives. The nationalist movement was driven, alive, and taking action.

Denshawai’s Legacy in Modern Egypt

Denshawai’s impact on Egyptian nationalist fervour was not limited to 1906 or even just the decade that followed. Fifty years later, Gamal Abdel Nasser addressed the newly independent Egyptian nation. He spoke about nationalizing the Suez Canal Company. In his speech, he criticized British arrogance. He referenced Lord Cromer’s rule (and by extension the Denshawai incident) to make his point. The Denshawai Museum was created to honor the incident. This, along with its inclusion in Egyptian school history curriculums, made it a key part of Egyptian history. It symbolizes the ills of colonialism and supports anti-colonialism, nationalism, and resistance.

Over time, the Denshawai incident and its trial have held various meanings for different people. All of these meanings were shaped by the stories told of the incident and about the different parties involved. British administrators and papers shaped narratives about fellaheen. These narratives created the setting for the trial that followed. On the other hand, Egyptian poets and newspapers created works that fueled the anticolonial movement. They showed that Denshawai was not a story of the savagery of Egyptian villagers, but their resilience.

Sources

Carcanague, Marc John. Death at Denshawai: A Case Study in the History of British Imperialism in Egypt, rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/36514/. Accessed 10 July 2025.

“The Denshawai ‘Incident’ 107 Years Later: A Symbol of Colonial Arrogance Unforgotten in Egypt.” MEI Editor’s Blog, mideasti.blogspot.com/2013/06/the-denshawai-incident-107-years-later.html. Accessed 10 July 2025.

“Egyptian Gazette (1906-07-05) .” Internet Archive, 5 July 1906, archive.org/details/egyptian-gazette-1906-07-05/page/8/mode/1up?view=theater.

“Incident de Denshawai.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 4 Dec. 2024, fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Incident_de_Denshawai.

Limited, Alamy. “Denshawai Incident Hi-Res Stock Photography and Images.” Alamy, www.alamy.com/stock-photo/denshawai-incident.html?sortBy=relevant. Accessed 10 July 2025.

“Middle East and Islamic Studies Collections: An Exhibition of Treasures.” Middle East and Islamic Studies Collections, Durham University Library, valentine.dur.ac.uk/me_exhibition/Dinshawi%20Incident/dinshawi2.htm. Accessed 10 July 2025.Shaw, Bernard. John Bull’s Other Island, and Major Barbara. Brentano’s, 1907.

About The Atlas

The Atlas is a blog by Kharita, dedicated to exploring topics in geography, history, and geopolitics, without the typical Western spin. We aim to offer fresh, grounded perspectives and welcome contributions from writers around the world, representing a diverse range of experiences and backgrounds.

عن الأطلس

الأطلس هو مدونة تابعة لـ خريطة، مخصصة لطرح مواضيع في الجغرافيا، والتاريخ، والجغرافيا السياسية، من غير الفلترة أو التحيز الغربي المعتاد. هدفنا هو تقديم رؤى جديدة وواقعية، وبنرحب بمقالات من كُتّاب من مختلف أنحاء العالم، بخلفيات وتجارب متنوعة.