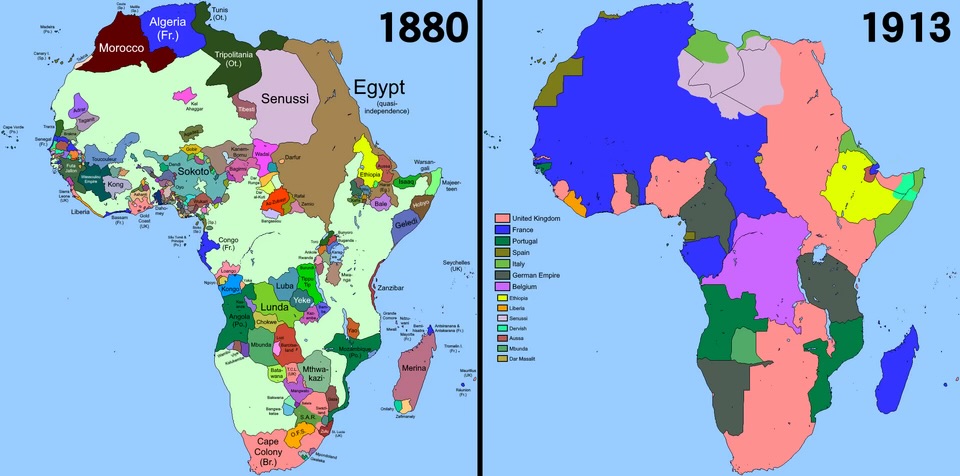

Maps and power aren’t often paired, but in Africa’s story, they’ve always walked hand in hand. Lines were drawn not to guide, but to divide and rule. Before colonialism, Africa was a thriving continent of kingdoms, empires, and autonomous nations, each governing its affairs according to its customs, laws, and leadership.

Territorial boundaries weren’t rigid lines on a map, but were often shaped by natural landmarks, such as rivers, lakes, deserts, and trade routes. Some regions, like North Africa, had more formalised cartography, influenced by Islamic or Middle Eastern traditions.

Unlike the visa systems across the continent today, people moved freely across regions, conducting trade, visiting relatives, or migrating in response to seasonal needs.

All that began to change in the late 19th century, when European powers drew up new borders of Africa for their gain.

What It Was Before The Divide

Africa was a trader’s paradise, rich in precious minerals, rubber, and fertile land that produced a variety of crops. This wealth and vibrancy made Africa the envy of many.

Across the continent, from the shores of Mombasa to the deserts of Marrakesh, from the bustling streets of Kano to the ancient city of Great Zimbabwe, markets overflowed with goods, stories, and ideas.

Centres of learning like Timbuktu housed thousands of manuscripts on astronomy, medicine, law, and philosophy.

Africans for long have been peaceful and welcoming, a trait that would later cost them. Cultures of different kinds co-existed, each with its unique way of life and monumental places named in indigenous languages with great meaning.

It wasn’t all peace; intertribal disputes did exist, as with any part of the world. However, mutual respect, alliances, and trade often overpowered the conflicts.

Africa was far from “uncivilised” or a blank slate that needed shaping, as European powers later claimed it to be. It was where civilisation began and had long flourished.

The Berlin Conference: The Scramble For Africa

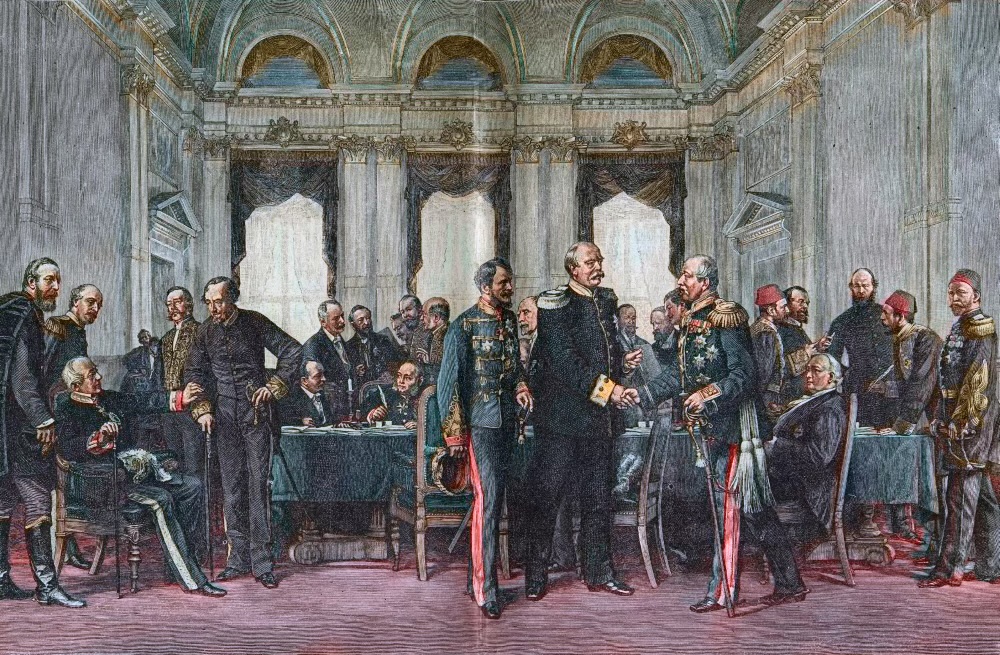

In 1884, German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck hosted the Berlin Conference, a gathering of European powers that would forever alter Africa’s fate. The goal? To divide Africa among themselves without going to war with one another.

The conference was partly sparked by rising tensions over the Congo Basin. King Leopold II of Belgium had claimed the area for himself, which upset other countries like France and Portugal. To avoid conflict, they agreed to sit down and make rules for taking African land.

At the Berlin Conference, 14 European countries (including Britain, France, Germany, Belgium, Portugal, and Spain) sat around a table and redrew the continent. No African was at the table. Seven (7) nations will later back out, while the others went on to colonise and divide the African continent afterwards.

Europe at the time, was going through rapid industrial growth and needed raw materials. Africa was a land brimming with natural wealth from every corner. Colonial leaders saw an opportunity to expand their power, extract resources, and tap into cheap labour.

They drew borders with little knowledge or care for Africa’s existing cultures, ethnic groups, or political systems. These borders ignored the continent’s deep history and interconnectedness.

Even though many of the borders we see today were finalised later, the decision made at the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 marked the beginning of modern Africa’s borders. Lines drawn by outsiders, for their benefit. The damage is still felt today, through ethnic conflict, weak governance, and economic struggles.

A New Way of Life, Rooted in Control

In the late 19th century to early 20th century, colonial governments were fully implemented. The borders drawn gave rise to deep-rooted tensions. Ethnic groups that had coexisted peacefully found themselves forced into single colonies with rival groups, while others were split across multiple territories.

People were forced to learn and speak languages other than their own. New systems were put in place, and those who resisted faced harsh consequences. Local communities lost their power in decision-making.

This disconnection gave rise to competition, mistrust, and, in some cases, violence. Colonial powers often practised divide-and-rule tactics, favouring one group over another in administration, access to resources, or military recruitment.

These seeds of division later grew into major conflicts such as civil wars, separatist movements, and ongoing regional instability, from the Rwandan genocide to the Nigerian-Biafran conflict and for many decades up till now, the War in Congo.

Economic disruption swept across Africa; traditional trade routes and economic systems were badly affected. The Sahel region’s trans-Saharan trade networks were cut by French and British borders. Herdsmen like the Fulani and Tuareg found their migration routes blocked.

Colonial economies prioritised cash export over local needs, which interfered with food production and caused hardship for the local population. Wealth flowed out of the continent, making it hard to access education, healthcare, and opportunity.

Even long after independence, many of these tensions remain unresolved.

Independence Without Withdrawal

As African countries began to gain independence in the mid-20th century, many inherited not only the borders but also the systems left behind. The European powers may have formally withdrawn, but their political structures, economic models, and languages remained entrenched.

Newly independent nations often lacked the tools or unity to reimagine more organic boundaries. And with the 1963 charter of the Organisation of African Unity (now African Union), countries agreed to respect colonial borders to avoid further chaos.

This decision was meant to preserve peace, but also cemented the very lines that had divided the continent. True withdrawal never happened; colonisation simply evolved into a more subtle form of influence, from foreign debt and resource extraction to soft power and diplomacy.

Unlearning the Lines

Today, many Africans are reimagining connections across colonial lines. Technology, travel, and Pan-African movements are helping rebuild kinship and collaboration once severed by colonial maps.

Young Africans are reclaiming languages, reviving traditions, and telling stories that predate colonisation. Though the borders remain, the spirit of resistance, unity, and renaissance continues to grow, proving that Africa is more than the lines drawn across it.

Initiatives like the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), established in 2018, aim to restore economic and cultural flow across regions.

The colonial borders of Africa were never meant to serve Africans; they were designed for control. Yet, despite the chaos they caused, Africa endures. The continent continues to adapt, reclaim, and resist, showing that identity runs deeper than geography.

About The Atlas

The Atlas is a blog by Kharita, dedicated to exploring topics in geography, history, and geopolitics, without the typical Western spin. We aim to offer fresh, grounded perspectives and welcome contributions from writers around the world, representing a diverse range of experiences and backgrounds.

عن الأطلس

الأطلس هو مدونة تابعة لـ خريطة، مخصصة لطرح مواضيع في الجغرافيا، والتاريخ، والجغرافيا السياسية، من غير الفلترة أو التحيز الغربي المعتاد. هدفنا هو تقديم رؤى جديدة وواقعية، وبنرحب بمقالات من كُتّاب من مختلف أنحاء العالم، بخلفيات وتجارب متنوعة.